How COVID-19 led to brain fog, memory loss and no sleep for this Kentucky 23-year-old

PLAY VIDEO: Dr. Daniel O. Lee, Kentucky Neuroscience Institute Medical Director, explains how he found a solution to cure a case of encephalitis, a swelling in the brain, caused by COVID-19

Shelby Ponder thought her bout with COVID-19 was nothing to write home about: her mild, strep-like symptoms cleared up in a few days.

As a healthy 23-year-old, she’s considered at low-risk of developing a serious infection from this disease. But her health determinants as a young person dictated less what came after: coronavirus-induced encephalitis, or brain swelling, which impacted her memory, eyesight, basic motor functions and impeded her ability to sleep for days on end.

“It was almost like this monster lurking in the shadows, just waiting to reemerge,” she said last week.

It’s very clear who’s at highest risk of death from COVID-19. People age 70 and older in Kentucky account for 74 percent of all coronavirus-related deaths. And generally, people living with other pre-existing health issues are at highest risk for bad infection.

But those same health determinants do not necessarily dictate who will develop sometimes debilitating long-term symptoms once the live virus is gone, a group of people that have come to be known as “long-haulers.”

Many in this group had relatively mild COVID-19 infections. A new study charting the progress of more than 1,400 people in California who tested positive but were never hospitalized found that more than a quarter continued to struggle with symptoms more than two months after their diagnoses. Of those long-haulers, a third were asymptomatic after testing positive.

This unknown has puzzled health care professionals and continues to fuel warnings for people not to let their guard down on a disease that has finally started to recede in Kentucky.

More than 29 million Americans — over 414,000 Kentuckians — have contracted the novel coronavirus. Though an exact number isn’t known, tens of thousands of people across the country, including some kids, are reportedly plagued with long-term side effects once the active virus has left their system. They experience a whole host of symptoms, ranging from heart and breathing complications, to neurological and mental health issues.

Sensing a demand to treat and learn more about this growing group of people, many hospitals around the country, including Norton Healthcare and University of Louisville, have opened post-covid clinics for patients with protracted side-effects. Late last month, the National Institutes of Health announced a new initiative to study and treat long-haulers, admitting, “we do not know yet the magnitude of the problem,” but given the volume of people who have been or will be infected, “the public health impact could be profound.”

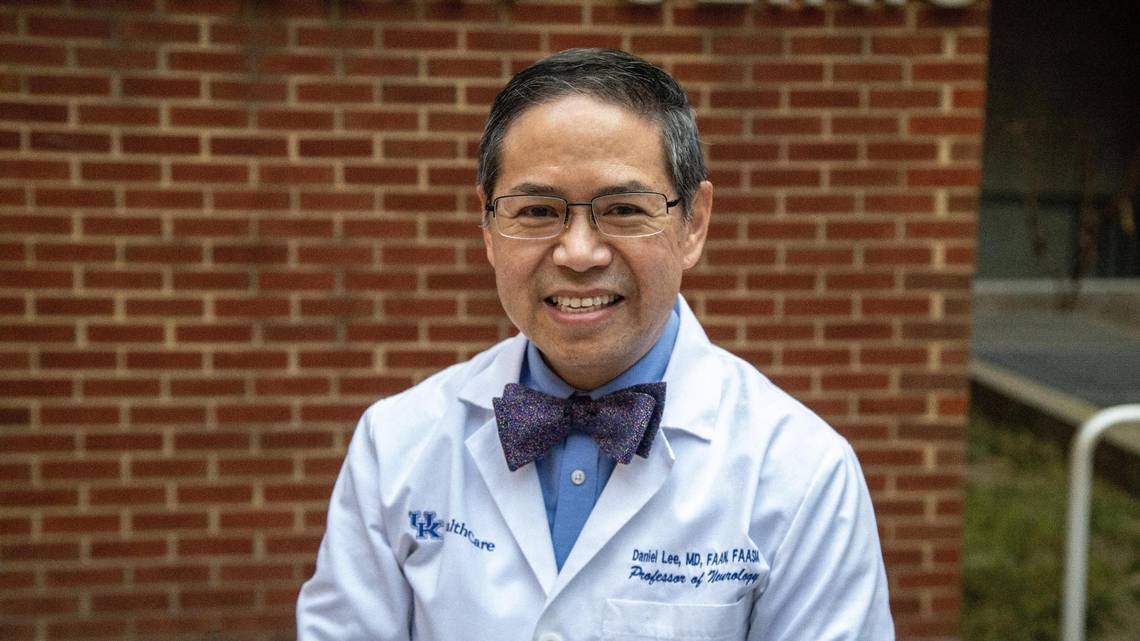

Dr. Daniel Lee, medical director of the Kentucky Neuroscience Institute and sleep specialist at the University of Kentucky, monitors patients with lasting neurological impacts after recovering from COVID-19. Their age and healthiness, he said, runs the gamut, making it difficult to predict who’s most at risk.

He estimates that 10-13 percent of people who test positive for COVID-19 will have some sort of brain impact from the virus, and are at risk of developing encephalitis. In Kentucky, that amounts to 54,000 people who may experience heightened drowsiness or sleeplessness, headaches, brain fog, and memory loss, depending on which part of the brain is affected. Many people may live with mild encephalitis and not know it, said Dr. Lee, who’s also vice president of the Commonwealth Neurological Society.

Experts don’t think the novel coronavirus directly attacks brain cells. Rather, the body’s robust autoimmune and inflammatory response it mounts to fend off the virus sometimes ends up destroying healthy tissue and leaving lasting inflammation.

That’s what happened with Shelby, a second-year law student at the University of Kentucky.

After learning she was exposed to a family member with COVID-19, Shelby developed mild cold-like symptoms, though she never tested positive. By July, she had recovered completely, just in time to start a coveted internship with the U.S. Attorney’s Office in London, near her home in Mount Vernon.

She started her internship, but something didn’t seem quite right. Her brain felt fuzzy. Two weeks in, she was asked to aggregate different court filings about when law enforcement can legally seize someone’s cell phone — a digital search aided by using keywords. Only, she couldn’t think of any.

“I remember just sitting in front of the computer for two or three hours, being like, ‘What do I need to search?’” she said of the task which “should [otherwise] be fairly simple for a second-year law student.”

That was when the second wave of strep-like symptoms hit, this time with a high fever in tow. She got tested again, just to be sure. It was negative. “From there, everything just deteriorated,” she remembers.

For the next week or so, her fever toggled between 103 and 103.9 degrees without breaking. She slept with bags of frozen vegetables around her head, at the suggestion of her worried mom. She slipped in an out of delirium, sleeping for most of the day, only waking to eat and shower.

That next week, as her fever persisted, they went to the emergency department at Baptist Health Lexington, where she again tested negative for coronavirus. Doctors did a series of other tests, none of which were conclusive.

She returned home for another week, but nothing changed. Shelby and her mom decided to try the health care system at University of Kentucky, but doctors were just as perplexed. She again tested negative and was sent home.

In a little more than a month, she visited three different hospitals, including two separate visits at UK. Throughout it all, she never tested positive for COVID-19. “No one really knew what to do,” she said.

Finally, by mid August, “a switch flipped,” and her fever broke, but not for long.

Right around that time, she noticed her vision began to blur and shake. The quality of her eyesight wasn’t deteriorating, she just couldn’t focus; it felt like her eyes were rattling. “If I was looking at somebody’s face, I couldn’t make out their features,” she said. “It was like my eyes were having an earthquake.”

While her brain fog and wonky eyesight should’ve been indicators something serious was happening, it didn’t register right away.

“It was hard to even remember what normal is like [when] you lose your baseline,” she said.

A few days later, her fever came back in full force. Shelby and her mom drove to UK for a third time. She was admitted, and this time when doctors examined her, they could actually see her eyes twitching. Understanding her symptoms to be neurological, they asked her to touch her pointer finger to the first joint in her thumb in rapid succession. She couldn’t do it.

“I knew what I had to do, and I obviously knew how to do it, I just couldn’t,” Shelby said.

Doctors scanned her brain and body, analyzed her blood and saliva, tested her for coronavirus, as well as for viruses out of the Caribbean and South America. All were negative. A few weeks later, she tested positive for coronavirus antibodies, giving doctors greater insight into what happened next.

Her brain scan showed significant swelling. She was diagnosed with encephalitis and meningitis, both of which are often caused by viral infections. Shelby was scared to know her brain was swollen, but thankful to finally have her illness named.

‘MY COMPREHENSION WAS GONE’

She was discharged after four or five days with a steroid pack and a slew of other medications. Exhausted, all she wanted was to sleep. But that quickly became impossible.

Almost overnight, her body’s need to sleep up to 20 hours a day was replaced with an inability to sleep barely at all. And the steroid pack sent her fritzing.

“I took that and it made me like a maniac,” she remembers. “I could not rest at all. I was so fidgety. I couldn’t sit down.”

Doctors now know that multiple parts of Shelby’s brain were swollen, including her hypothalamus, where the sleep center is, and the part of her brain that produces melatonin, which helps her body transition to sleep.

Picture it like this, Dr. Lee said: if the brain was a car, one’s sleep center is the brake. If this part is barely functioning, as Shelby’s was, because of inflammation, there’s no way to slow the body down and reset. The steroids she was prescribed sent her into overdrive.

After a week of being unable to sleep for more than 30 minutes at a time, she went back to UK a zombie, utterly exhausted and on the verge of a mental breakdown. “I got to feel like it was not going to get better, and there wasn’t a legitimate cause,” Shelby said.

At UK, doctors wondered if Shelby was in steroid psychosis, still not linking the effect of the steroids with her brain swelling. That’s when she met Dr. Lee, a neurologist who’s also a sleep specialist. He looked at her brain scan, saw where the swelling was, and understood why she wasn’t sleeping: her sleep center just wasn’t working. Back to the car analogy: “The only way you can fix that is basically to ease off the accelerator,” he said. “We just wanted to find some time for the brain to heal itself,” he said.

Dr. Lee swapped most of the medications she’d been prescribed, which were exacerbating her sleep troubles, and put her on a tapered approach of other prescriptions. Slowly, Shelby was able to sleep for three and four hours at a time.

She wasn’t able to regularly sleep through the night, uninterrupted, until the fall, when she finally tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies. Her brain fog, too, persisted for several months after she started seeing Dr. Lee. She returned to school, but it was slow-going.

“I could not for the life of me recall simple legal stuff,” she said. “I couldn’t read at all. If I would get through a full page of reading, I didn’t have any memory of what I read. My comprehension was gone.”

But her youth ultimately worked in her favor. Encephalitis is “one of the most devastating neurological conditions,” and many people who develop it do not make a full recovery, said Dr. Lee, who continues to work with post-covid patients whose encephalitis has transformed into epilepsy or loss of controlled motor functions.

Part of the challenge in treating these and other acute post-covid symptoms is a struggle to diagnose them, Dr. Lee said. “I just hate that people like Shelby are suffering but are not getting care. We don’t know how many more are out there because they have been told by so many places that it’s not fixable.”

Now, eight months later, Shelby is still not entirely back to normal, but she’s much closer to it. She just stopped taking her last sleep medication, she’s engaged, and after months of wondering whether it would happen at all, she has resumed planning her May wedding. Dr. Lee, who calls and checks on her daily, is invited.

For Shelby, life was forever altered by this disease, and “it can be hurtful” to see people not take it seriously.

“I think that’s the hardest thing,” she said. “It’s completely preventable and it’s [infecting] more people every day, but it doesn’t have to.”