During Indigenous Peoples’ Month, the UK College of Medicine is highlighting historical figures who paved the way for an equitable future in medicine.

Susan La Flesche Picotte (1865-1915)

Born in Nebraska in 1865, La Flesche would go on to graduate second in her class from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia, now Hampton University. Addressing the crowd during her graduation speech, she said “We who are educated have to be pioneers of Indian civilization. The white people have reached a high standard of civilization, but how many years has it taken them? We are only beginning; so do not try to put us down, but help us to climb higher. Give us a chance.” Three years later, La Flesche became a doctor. She graduated as valedictorian of her class and returned to the Omaha reservation where her yearly salary was merely $500, 10 times less than army or navy doctors were receiving. Despite poor compensation, she founded a private practice to treat both white and Native patients and devoted her career to promoting change and improving conditions on reservations. She was an enduring advocate for alcoholism prevention on the reservations and persuaded the Office of Indian Affairs to ban liquor sales in towns formed within the reservation boundaries. She advocated proper hygiene and the use of screen doors to keep out disease carrying flies, waged unpopular campaigns against communal drinking cups and the mescal used in new religious ceremonies. And before she died in September 1915, she solicited enough donations to build the hospital of her dreams in the reservation town of Walthill, Neb., the first modern hospital in Thurston County.

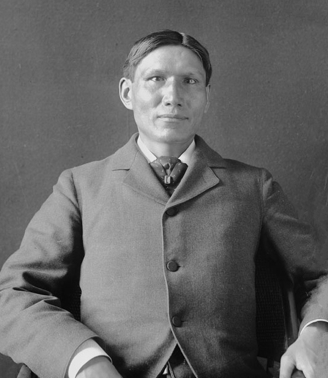

Carlos Montezuma (1866-1923)

At five years old, Carlos Montezuma was kidnapped from his Yavapai family in Arizona and sold to a photographer named Carlos Gentile for 30 pieces of silver. Upon adopting him as a son, Gentile changed Carlos Montezuma’s name from his Yavapai birth name, Wassaja. Eventually the pair would settle in Chicago, where Montezuma’s official education began. He graduated from Chicago Medical College in 1889, becoming the first Native man to earn an MD degree, just years after Susan La Fleshe. From 1889 through the end of 1892 Montezuma worked as a Bureau of Indian Affairs physician at reservations in the Dakota Territory, Nevada, and Washington State. In 1896 Montezuma returned to Chicago where he set up an independent medical practice and taught at various medical schools. He would remain a practicing physician in Chicago for more than twenty-five years. Montezuma's service at Indian Affairs hospitals in the West influenced his work as an author as well. His advocacy efforts gained him national prominenc— his speech “Let My People Go” was read in Congress in 1916 and appeared in the Congressional Record. From 1916, until his death in 1923, he published his own newspaper, WASSAJA, which called for the abolition of the Office of Indian Affairs. In December of 1892 Carlos Montezuma returned to his Yavapai homeland in Arizona and on January 31, 1923 he died there from tuberculosis.

Charles Eastman (1858-1939)

Charles Alexander Eastman, a Santee Sioux Indian, was the first Native American to be certified in Western medicine. He was also a prominent Native writer, national lecturer, and reformer. At age four, the Dakota War of 1862 separated him from his family. For years, he learned the traditional ways of hunting and being a warrior from his tribe. At 15, his father suddenly reappeared in his life, having converted to Christianity. He encouraged his son to do the same. Born with the name Ohiyesa, the teen changed it to Charles Eastman before beginning his formal education. He would attend Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois, and Kimball Academy, and Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1887 and immediately entered the Boston University School of Medicine, where he received an M.D. degree in 1890. After marrying, he moved to St. Paul, Mn., to set up a private practice. Private practice brought with it several financial challenges, so Eastman began to write. Eastman was also involved in establishing 32 Indian groups of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Eastman published a memoir entitled Indian Boyhood in 1902, which recounted his first fifteen years of life among the Sioux. During the next 20 years, he would write ten more books, most concerned with his Native American culture. His writings and work with the YMCA prompted the founders of the Boy Scouts of America to request his assistance. From 1923-25, Eastman served as an appointed U.S. Indian inspector under President Calvin Coolidge. His recommendations would later serve as the basis of the Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal for the Indians, which sought freedom and self-determination.

Inventions That Changed Medicine

Adapted from Forbes:

Below are seven inventions used every day in medicine and public health that we owe to Native Americans.

Syringes

In 1853 a Scottish doctor named Alexander Wood was credited for the creation of the first hypodermic syringe, but a much earlier tool existed. Before colonization, Indigenous peoples had created a method using a sharpened hollowed-out bird bone connected to an animal bladder that could hold and inject fluids into the body. These earliest syringes were used to do everything from inject medicine to irrigate wounds. There are also cases in which these tools were even used to clean ears and serve as enemas.

Pain Relievers

Native American healers led the way in pain relief. For example, willow bark (the bark of a tree) is widely known to have been ingested as an anti-inflammatory and pain reliever. In fact, it contains a chemical called salicin, which is a confirmed anti-inflammatory that when consumed generates salicylic acid – the active ingredient in modern-day aspirin tablets. In addition to many ingestible pain relievers, topical ointments were also frequently used for wounds, cuts and bruises. Two well-documented pain relievers include capsaicin (a chemical still referenced today that is derived from peppers) and jimson weed as a topical analgesic.

Oral Birth Control

Oral birth control was introduced to the United States in the 1960’s as a means of preventing pregnancy. But something with a similar purpose existed in indigenous cultures long before. Plant-based practices such as ingesting herbs dogbane and stoneseed were used for at least two centuries earlier than western pharmaceuticals to prevent unwanted pregnancy. And while they are not as effective as current oral contraception, there are studies suggesting stoneseed in particular has contraceptive properties.

Sun Screen

North American Indians have medicinal purposes for more than 2,500 plant species – and that is just what’s currently known between existing practices. But, for hundreds of years many Native cultures had a common skin application that involved mixing ground plants with water to create products that protected skin from the sun. Sunflower oil, wallflower and sap from aloe plants have all been recorded for their use in protecting the skin from the sun. There are also noted instances of using animal fat and oils from fish as sunscreen.

Baby Bottles

It wouldn’t be considered sanitary – or safe – by today’s standards, but long before settlers made their way to American lands, the Iroquois, Seneca and others created bottles to aid in feeding infants. The invention consisted of the insides of a bear and a bird’s quill. After cleaning, drying and oiling bear intestines, a hollowed quill would be attached as a teat, allowing concoctions of pounded nuts, meat and water to be suckled by infants for nutrition.

Mouth Wash & Oral Hygiene

Although tribes across the continent used various plants and methods for cleaning teeth, it is rumored that people on the American continent had more effective dental practices than the Europeans who arrived. In particular areas, mouthwash was known to be made from a plant called goldthread to clean out the mouth. It was also used by many Native cultures as pain relief for teething infants or a tooth infection by rubbing it directly onto the gums.

Suppositories

Hemorrhoids are nothing new. Nor is the pain and discomfort associated with having hemorrhoids. But before modern-day solutions and dietary changes, Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas created suppositories from dogwood trees. Dogwood is still used today (although not often) externally for wounds. But hundreds of years ago small plugs were fashioned by moistening, compressing and inserting the dogwood to treat hemorrhoids.

Additional Resources:

From Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC): Attracting more Native American students to medicine

From American Medical Association (AMA): Native Americans work to grow their own physician workforce

From Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME): Part 1 American Indian and Alaskan Natives in Medicine Webinar; Part 2 American Indian and Alaskan Natives in Medicine Webinar

Resources below provided by ACGME Equity Matters Series:

Articles

Report Catalogs Abuse of Native American Children at Former Government Schools

Horrors Pile Up Quietly In ‘The Other Slavery’

Does the ‘Bamboo Ceiling’ Shut Asian Americans Out of Top Jobs? (NPR)

Unnatural Causes… Is Inequality Making Us Sick?

Books

Keepunumuk: Weeachumun’s Thanksgiving Story

Go Back to Where You Came From: And Other Helpful Recommendations on How to Become American (Ali)

This is Their Land

Podcasts

This Land | Crooked Media

Reflecting on Dine’ College; Doctoral Education; Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Additional Resources

Equitable Care Interpretation

List of Federal and State Recognized Tribes

Minority Health- Profile: American Indian/ Alaska Native

Native American History and Culture- Boarding Schools

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Department of Interior Releases Investigative Report, Outlines Next Steps in Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative