The Gross Room

Would you dare enter the gross room? What if you knew what was in it – containers of organs and tissue samples? Those who do go in find it either interesting or, well, gross, said Shawna Baker, MBA, PA (ASCP)CM, associate director of anatomic pathology at UK HealthCare.

UK HealthCare’s gross room is the point of inception for organs and tissue samples en route to pathological diagnosis. The histology/surgical pathology team is responsible for facilitating the progression from raw-tissue delivery to the point that the processed tissue is placed on a microscope slide for diagnostic viewing by a pathologist.

A Hundred Biopsies a Day

When a patient has a biopsy of skin or internal tissue, it first goes to a grossing technician, pathologists’ assistant or surgical pathology resident who describes each specimen by its size and appearance. They dissect the larger organs according to established protocols and send them to histology, where the specimens are prepared for light microscopy. Histotechnologists load the “blocks” of tissue onto processing instruments that remove water from the tissue and replace it with melted paraffin wax. The wax infiltrates the tissue and provides the necessary support the histotechs need when cutting the tissue into the thin slices that will be examined under a microscope by a pathologist.

“On average, we probably have about 100 cases come through surgical pathology a day, and then each case can have a varying number of parts,” Baker said. “If someone goes through an endoscopy procedure, they can have one or 10 biopsies done, so those 100 cases usually equate to between 400 or 600 paraffin blocks for the histology team to process and prepare for our pathologists to examine.”

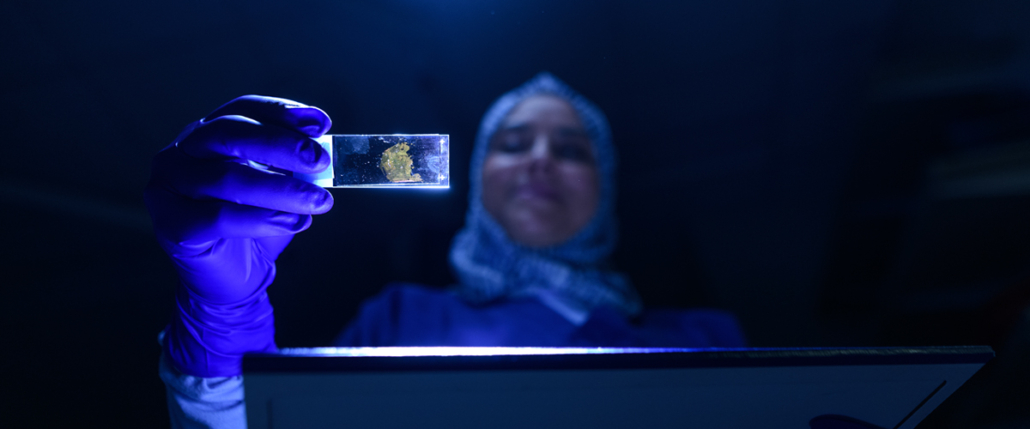

Histotechnologists use a specialized machine called a microtome to cut thin sections of the tissue that has been embedded in the wax block. These sections are cut one after another to form a ribbon, which is floated on warm water to soften and flatten the sections. These sections are then placed on microscope slides and stained. When staining is completed, the tissue section is ready for examination under a microscope by a pathologist.

Generally, it takes 24 to 48 hours from the time the tissue is received in surgical pathology before a diagnosis is ready, with the exception of more difficult cases that require consultation or further testing.

“If the pathologist decided it’s cancer but is not sure what type, they can order immunostains [from the immunohistochemistry lab],” Baker explained. “We cut additional slides off of the paraffin block and order special immunostains that can narrow it down to a more specific type of cancer, or determine whether it was primary cancer versus metastatic cancer.”

There are also times, however, when a preliminary or rapid diagnosis is needed while a patient is on the operating table. In surgical pathology, these STAT procedures are called “frozen sections” or “intraoperative consultations.”

“When one of those specimens comes into the room, we drop whatever it is we’re doing and handle it right then and there,” Baker said. “Frozen sections are performed when a surgeon wants to know if the margins of his or her resection for a malignant neoplasm are clear before closing, when an unexpected disease process has been found and the surgeon needs a diagnosis to determine how to proceed, or to determine if appropriate tissue has been obtained for further workup of a known disease process. This technique provides a rapid diagnosis, generally within 20 minutes of when the tissue is received in surgical pathology.

“The tissue sample is brought to surgical pathology ‘fresh’ or ‘dry,’ without any type of fixative or solution on it,” Baker continued. "It is frozen at -20 degrees within a gel-like embedding media in the cryostat, and cut into thin sections that are placed on the slide and stained for the pathologist to view under the microscope. It is not the ideal way to process tissue, but it provides adequate results for the pathologist to typically render an immediate interpretation that can guide the surgeon on how to proceed. It does not replace the paraffin-embedding process. All tissue submitted for frozen section is then submitted to histology for permanent processing.”

Meeting the Mission of Care, Education, and Research

In addition to clinical diagnosis, the histology/surgical pathology team is very involved in research and education. Residents preview tissue cases for learning purposes, and investigators at the UK Center for Clinical and Translational Science Biospecimens Core will collect tissue samples for specific studies.

“A lot of times, researchers need slides to test their research methods,” Baker said. “They can also extract DNA from tissue to [help in the development of drugs] that target specific gene mutations.”

This is one reason the histology/surgical pathology lab stores paraffin blocks and microscope slides for 20-plus years. Additionally, if a patient is diagnosed with cancer and goes into remission after treatment but has a reoccurrence many years later, a new biopsy can be compared to the old one to determine whether it is primary or metastatic cancer, and to possibly aid in treatment options.

Regardless of what others think of their workspace, the histology/surgical pathology team undoubtedly finds the gross room intriguing. More than that, however, they are committed to helping patients get on the right path to healing.

This story was originally published in the September 2019 issue of Vital Signs. Read the full issue here.