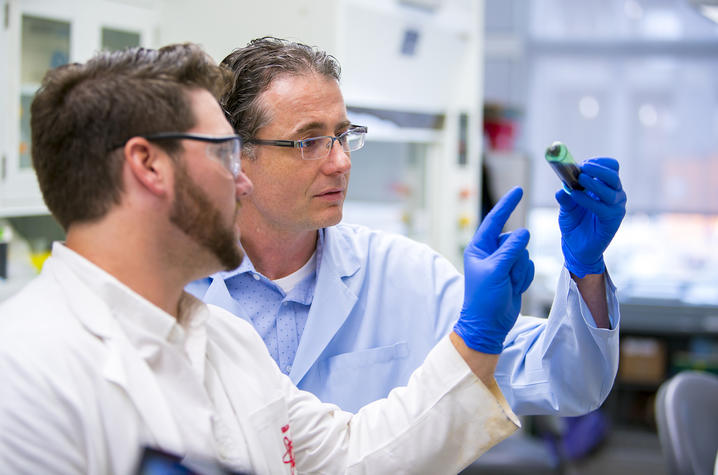

The People Behind Our Research: "You Have to Follow the Science Where it Takes You"

A peek at Matthew Gentry's professional profile reveals a long list of honors and awards.

- A National Science Foundation Faculty Career Development Award.

- A National Institutes of Health Pathway to Independence Award.

- A University of Kentucky Research Professorship Award.

- Three U.S. Patents.

- A five-year, $8.5 million National Institutes of Health grant to pursue a cure for Lafora disease.

Wait. Lafora disease? From a lab that also studies biofuels?

"I began my career studying plant proteins and am now working on human diseases," Gentry says. "You have to be willing to go where the science takes you."

In Gentry's case, the journey began when he found that a certain plant protein behaved similarly to the human protein implicated in Lafora disease. This discovery provided information that medical researchers around the world are using today to test potential therapies for this deadly congenital form of epilepsy.

The research was also a step toward the development of methods to modify starch, with applications in the manufacture of such varied products as plastics, animal feed, glue, and clothing.

On a molecular level, the overlap between plant and human biology is tremendous. "Not long ago, the prevailing thought was that you could either work to cure a disease, or you could work to figure out how something [a plant, a cell] functions," Gentry says. "We are now at the point where the two intersect."

Gentry spends a great deal of his time advocating for more science funding through his work with the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. The current funding landscape is such that scientists must spend more and more of their time writing grants, which takes them away from doing the meaningful work, he explains.

He also hopes that more of those dollars will support the types of basic research that shed light on cellular function and dysfunction.

"This type of research can have implications for many diseases, not just one," he says. "We need to be careful not to silo all the research dollars for specific diseases because that sometimes doesn't allow the best science to get done."